by Will Lowry, originally published in The National Interest. Listen to the whole episode on Press the Button.

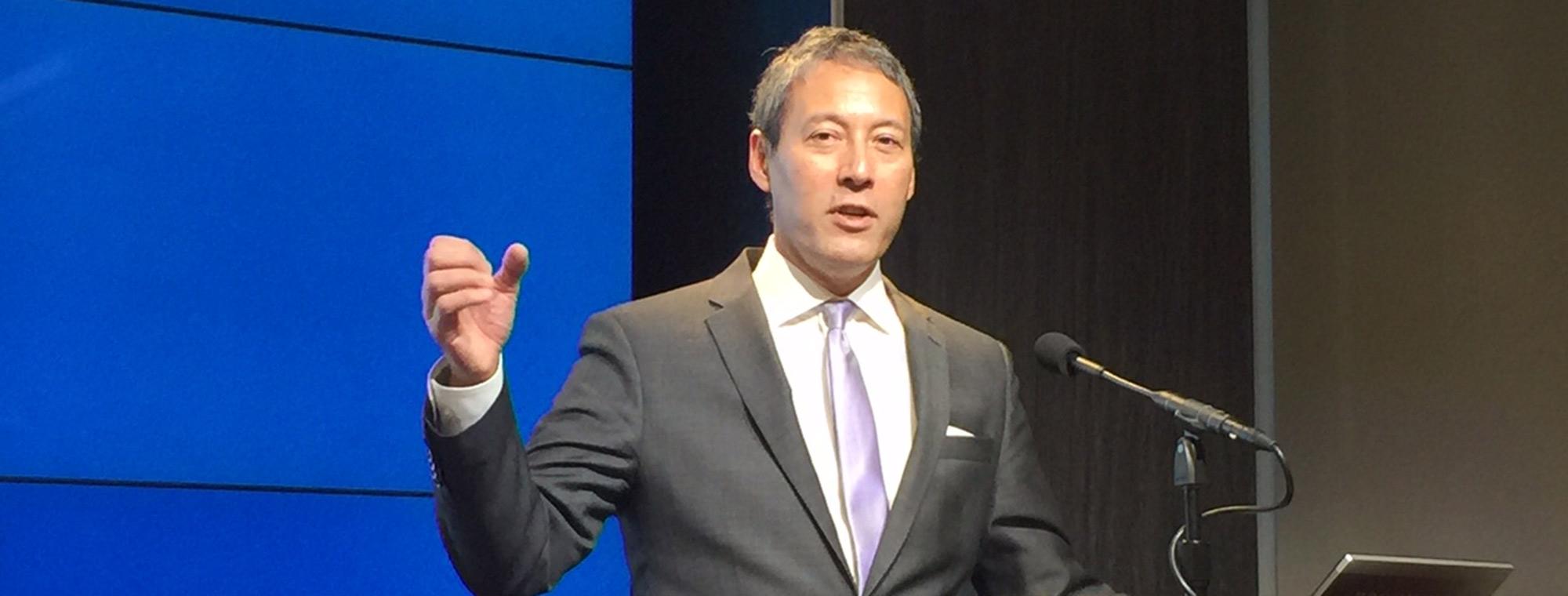

In this week’s episode of Press the Button, author, professor and expert David Kang discussed the widespread, bipartisan call in U.S. foreign policy and defense planning to move from the ‘war on terror,’ to increased confrontation—especially with China. The idea of a return to great-power competition is related, by its proponents, to calls for national renewal, technological innovation, and a change in military posture such as moving forces from the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific region, with an “increasingly aggressive” China as the rationale.

David Kang is Maria Crutcher professor of international relations at the University of Southern California (USC) and director of the USC Korean Studies Institute. On the podcast, he was asked about recent developments in East Asia and what he thinks about the “ramping up” of rhetoric in the United States. Policymakers increasingly speak of China as if it were an existential threat to the United States. “At most, China is a threat at the margins of the territorial grid over some disputed rocks that nobody lives on in the middle of the ocean,” Kang said.

Kang expects this anti-China frame to be the guiding principle for U.S. foreign policy in the region because “just like with North Korea, it is very easy to look tough.” This “look tough” approach is short-sighted—and possibly even tragic—because diplomacy, although difficult, might be far more likely to yield positive results over the next few decades. As an example, he said, “We are in the same place on North Korea that we've been for decades, which is a tragedy, but essentially the choices are the same as they've always been. Do we pressure them? Sanctions? Try and contain? Or do we engage them and try and use diplomacy and open them up.” In moving the frame away from “anti-China” to a place that would increase global security, the primary difficulty is that a “pro-diplomacy” frame would require diplomacy. Diplomacy presents a relative difficulty because the U.S. congressional-industrial-military complex makes “looking tough” seem effortless, as long as the military budget is large—and not only is it quite large, but growing.

Kang also connected this simplistic desire to look tough and militaristic with racism—specifically against Asian Americans: “Almost daily somebody's writing about this. Just the other day, a mainstream CSIS think tank scholar said, ‘we should keep Chinese students out of America because they’re going to infiltrate our country.’” An increasingly evident anti-China frame coincides with a rise in anti-Asian speech and violence, particularly following the onset of the coronavirus in the United States, where anti-Asian and anti-Chinese racism have a long history.

When asked about the link between the anti-China frame and recent violence and aggression towards Asian Americans, Kang talked about racism as a kind of “unknowing.” Kang said, “the link between the two is really interesting because, first of all, nobody distinguishes between, say Chinese, Korean or Japanese—they’re all Asians, and so violence against all of them is sort of indiscriminate.” Secondly, he mentioned that racism against Asians is connected to the racist idea of “the perpetual foreigner” and sometimes even a “fifth column.” “It plays to a number of sort of caricatures of East Asians as being untrustworthy, secretive, inscrutable,” Kang said. “So, if on the domestic front there [is] a danger, then how can we know what China wants? They're just not like us, and it comes from the same type of unknowing rather than actually knowing what's going on on the ground.”

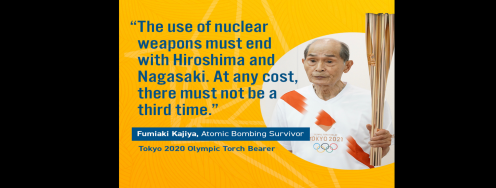

Returning to international relations in the context of “unknowing,” Kang said that, “in many ways, the idea that we are going to contain China and pressure them fits some Cold War conceptions, but it doesn't fit the reality of what's going on in East Asia.” China cannot be contained within its borders in the Asia-Pacific region. “Let me give you an example, he continued. “If we want to solve the North Korean issue—which is much bigger than nuclear weapons, by the way, it's human rights, it’s economy it's everything—if we want to solve that there's no possible way to do that without having China on board.” Kang further suggested that the United States would profit from a perspective that views these countries “not as problems to be solved, but as countries we have to live with.” As an example of a more pragmatic, perhaps even less-racist, approach that could advance U.S. security interests in the region, Kang said, “there is no combination of threats and carrots that is going to make North Korea open up, denuclearize, stop human rights abuses and disappear. That's not going to happen.” While we don’t have to like it, the United States may have to live with North Korea—and China.

The entire interview with David Kang is available on Press the Button.

Will Lowry is digital communications manager at Ploughshares Fund where he focuses on expanding Ploughshares Fund’s online presence and target audience, thereby expanding its supporter base and the impact of its campaign work. Prior to joining the team, Will worked for fifteen years managing digital communications for businesses and environmental organizations. Most recently, he assisted the Sierra Club with online activism and all areas of their work in the San Francisco Bay Area. Will holds a BA in English from UC Berkeley and a MA in Literature from San Francisco State University.

The entire interview with professor David Kang is available here on Press the Button.