Interview: “My Dad Moved the Mormon Church on Nukes”

September 3, 2025

This interview was conducted by Taylor Barnes for Inkstick Media—a Ploughshares grantee.

The Northrop Grumman Bacchus facility in Magna, Utah. Photo by Kim Raff for Inkstick Media

A few years ago, I came across what folks in Utah call “the MX battle,” and ever since, I can’t unsee it. The reason I keep coming back to it is not just because it’s a rare success story in the peace and disarmament space. It’s also an example of when grassroots organizing and public opinion actually changed the course of endless war in America.

I recently dug up the contact for the son of the progressive Mormon attorney who was behind a linchpin moment in the MX battle: a quiet lobbying campaign of Latter-day Saints church leadership that led the latter to, in 1981, fax a statement directly to then President Ronald Reagan’s administration opposing the project to base mobile nuclear missiles on rail tracks across Utah and Nevada. Church leaders expressed opposition not just to the specific missile but nuclear weapons as a whole, calling weapons of mass destruction a “denial of the very essence of that gospel” that brought Mormons into the area. The following year, the government scrapped the mobile “shell game” proposal and greatly scaled down the MX.

A colorful coalition of Utah and Nevada civil society members — including Native Americans, homebuilders, cattlemen, and hippies — came together to oppose the project, but the LDS dissent was seen as a critical turning point in a state that was about 70% Mormon.

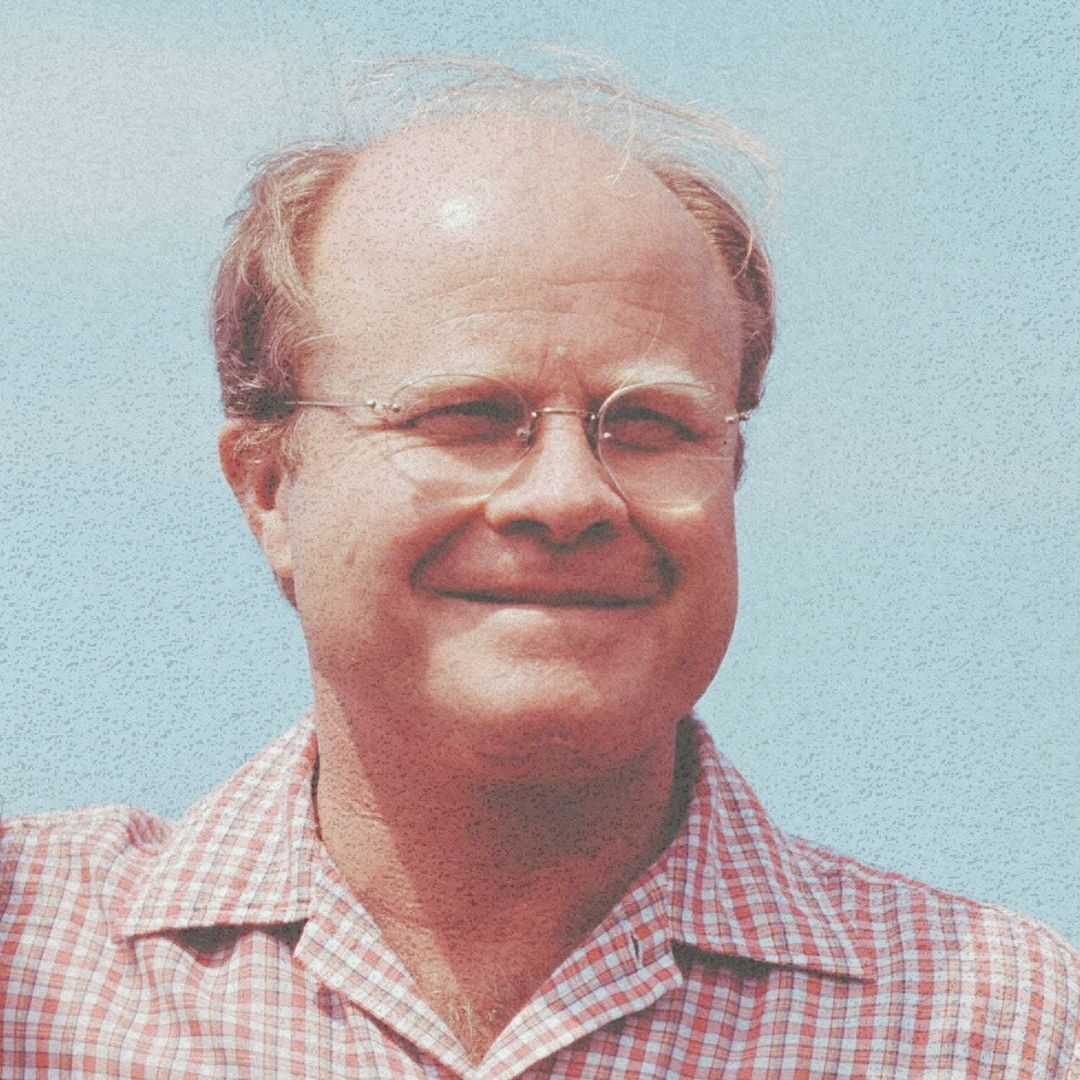

Behind that was a charismatic Mormon attorney, Ed Firmage, a descendent of Brigham Young. His LDS pedigree gave him access to the conservative church’s highest echelons even as he spent most of his professional and personal life in leftist social circles that included anti-war nuns, the Dalai Lama, and the NAACP. He also served as a White House fellow in Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration before becoming a law professor at the University of Utah.

Firmage Sr. passed away in 2020, and I recently spoke with his son, Ed Firmage Jr., about his father’s successful lobbying campaign.

Your father largely acted alone when he began lobbying Latter-day Saint leadership. How did he do it?

There were others, of course, involved in the anti-MX effort across civil society, but his relationship with the church was singular and very personal. His grandfather, Hugh B. Brown, was a member of the church’s top governing body called The First Presidency. The fact that Dad had an open door with church leadership says something not only about Dad’s connection, but also about the very different style of church leadership that existed at the time. It was still more a family than a political or economic institution.

So during the MX battle, Dad was trying to set a philosophical and also sort of procedural foundation for what would certainly be an unusually political statement on the part of the church. And he knew they would be very reticent. So he was trying to educate them in ways that would give them the courage to act. In one of the many in-person meetings that he had with the First Presidency, he had prepared a large packet of reading materials. This was with Spencer Kimball, the president, and his two counselors, Marion G. Romney and Eldon Tanner. And when Kimball saw the large packet of materials, he put his hand on Dad’s knee and said, “Eddie, you have to understand that we are basically blind. You just take your time and you tell us what you think we need to know.”

So that was the kind of connection they had. To their credit, even though I’m sure that they could be as bureaucratic as any organization, there was a willingness to act personally and to trust the person. And that provided Dad with this really unprecedented opportunity to educate them, to bring them along, and ultimately, to get them to make a series of increasingly important statements.

It was so influential. Your father later wrote that, “The MX debate and conclusion dramatically affected American nuclear policy, and hastened, I believe, the end of the Cold War.”

It’s a huge success story. Certainly from my vantage point, this was not only Dad’s crowning achievement in a career devoted to disarmament and peace studies. But it was also a huge environmental win in defeating the land-based mode that the Air Force had promoted. He saved the Great Basin. Between what the church did and what Dad did, they prevented the ecological catastrophe that the land-based system would have been.

What were some of your father’s entry points to persuade church leadership?

A few years prior to the whole MX thing, Dad had been given access to a lot of personal materials belonging to another Mormon apostle by the name of J. Reuben Clark, who had denounced the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as “fiendish butchery.” He had been an advisor to the World War II-era LDS church president as a member of the First Presidency and is still highly regarded in the church — the law school at Brigham Young University is named after him.

Shortly after the atomic bombings, he said, “God will not forgive us for this.” And he said it not in a private remark, but in the semiannual Mormon general conference. So the relevance of that was that Clark, like Dad, spoke not only as a Mormon leader, but also as someone with extensive government experience. He had been the US ambassador to Mexico and a legal counsel to the Department of State and negotiated treaties.

Dad was able to offer Clark as a precedent to church leadership. And what Dad realized early on and really leveraged was this idea of precedent. If you want to get conservatives to say something, to do something that seems out of character, find a precedent, so it seems more in character.

Were there other grassroots Mormon groups that were active on the MX missile?

In March, protestors at the Utah state capitol took part in a Latter-day Saints Renounce War and Proclaim Peace rally and sit-in. Photo courtesy of Mormons with Hope for a Better World.

There were individual progressive Mormons who felt similarly, but no Mormon grassroots organization. There were several ecumenical groups, and also an umbrella group called Utahns United Against MX, that Dad and my Mom were instrumental in founding

There was another national group called Clergy and Laity Concerned. It was a real hodgepodge of different groups opposed for quite different reasons to the MX. It included representatives from Native American tribes who were concerned about what this would do to their homeland. It included ranching interests who were similarly concerned about the environmental impact, as well as other church groups. So they had formed independently of Dad. But when Dad started speaking out publicly and writing publicly, they approached him about joining their group, as Dad liked to put it, as the “token Mormon.”

And it was kind of a token, because sadly, when Dad started speaking out, around 1978, pretty much the entire state of Utah — down the line, Republican, Democrat, state leaders, city leaders — everybody was in favor of the MX missile

I mean, even Utah’s Democratic Governor Scott Matheson was behind it. It seemed utterly quixotic to take this on where there was substantial political unity behind the program. It was about 80% of the state, according to polls, that were behind the MX system. And by the time the church spoke, that number had been flipped.

Who was the hardest to convince on the church side?

There was a super conservative member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles named Ezra Taft Benson. He was a longtime proponent of John Birch politics and opponent of Dad’s, dating back to the 1960s when Benson was trying to disseminate John Birch-style politics. They frequently butted heads. At one point, for example, Dad discovered that Benson had put together a John Birch movie to show in the church’s secondary-school seminaries. Dad happened to be on the board of the young men’s and women’s organization, and threatened to resign and make a public stink. This was unheard-of in Mormon insider institutional culture. The movie was set aside.

But in one of the meetings that Dad had with the Twelve over MX, at the end, as he was leaving, Benson came up to Dad and put his hand on Dad’s shoulder and says, “Brother Firmage, the Lord will bless you in this work.”

I think Dad was able to appeal to even deeper instincts in people like Benson around core values. And the thing about MX is that it threatened to just obliterate the core values of Utah community, Western community. And Benson had been Secretary of Agriculture under Eisenhower. So, he kind of represented that old style, pre-corporate Mormonism that was very agrarian and based in what we would now call sustainability and self-reliance,

But I think with Benson, it wasn’t just nuclear “NIMBYism.” It was: This is something that can destroy everything we’ve worked for as a people. Brigham Young and so many subsequent iterations of Mormon leadership had stressed that what the Mormon experiment was about was creating the Kingdom of God here in the American West. And that idea was not totally dead.

It’s pretty dead right now. But at this point, in 1978, with old-guard people like Benson, this was a threat to everything that they had worked for.

Do you think the church was proud of the role that it played in nuclear disarmament?

I think there was a sense that they had done something important. And I think there was an institutional awakening to that key issue of precedent, because in subsequent years, the anti-MX statement was used by the church as a precedent to take what would otherwise be perceived as political action.

Dad’s perspective was more typical of early Mormonism when it wasn’t simply a denominational organization, but a nuts-and-bolts, practically oriented attempt to reshape life from the ground up and to do so across all dimensions of life. Mormonism is different from most American denominations in that way. Early Mormonism saw itself not simply as a belief system but as a day-to-day way of remaking life. Including through polygamy and communitarian economics that made Mormonism so unappealing to many Americans. It’s going to be as interested in how you grow your gardens and organize your cities as it is in what you believe and profess in church.

So Dad’s view was: If it’s really important, then of course the church should speak out. If your faith doesn’t draw you to take care of the poor and the planet, it’s not much of a faith. Certainly it’s not a prophetic faith.

There was an aspect of the NIMBY issue that the liberal press did not really appreciate. For example, the New York Times was very critical about “the Mormon church just doesn’t want it in their backyard.” Well, for one, I’m sure you wouldn’t want a nuclear installation on the Hudson. But also, what the New York Times didn’t get is that this backyard has to do with fundamental identity.

Did you Dad ever try to push the church on any other contentious issues?

There were two moments of similar scope in Dad’s life. The MX was one big one, and then in 1989 there was another. Dad was invited to give an address at the Cathedral of the Madeleine, called the McDougall lecture. This is March of ‘89, still several months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Dad was scheduled to talk about arms control, and he was going to give a speech like the one that he would often give around the issue of loving your enemies and finding common cause, but events in his own personal life intervened to change the nature of what he said, and the address ended up being more generally framed around the issue of reconciliation.

And he talked not only about the issue of disarmament and détente with the Soviets, but also other things like women and the priesthood. And he famously, or infamously, said, “I look forward to the day when I see four women on the podium, right among the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, three of them Black.”

That speech earned him death threats. There was a Soviet delegation in Utah at the time. They were touring weapons facilities. So, in the wake of the furor that this reconciliation speech created, the State Department determined that it wasn’t safe for these Soviet visitors to have dinner with my parents, which had been on the agenda.

That reconciliation speech, for many Mormons, was a more significant event than the MX.

Currently, two Mormon-led anti-war campaigns, spurred by US support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza, are trying to influence both everyday Mormons and the church’s investment arm. One campaign has sent hundreds of letters straight to the investment manager, Ensign Peak Advisors, calling on it to divest from weapons manufacturers like Lockheed Martin and Boeing. Do you think the leaders of a church that once took such an influential position in favor of disarmament will be open to them?

Honestly, probably not. For a host of reasons. The historical Mormon church, even though it always had a strong, global evangelical reach, had always been very insular. And that’s a huge negative and also a positive, in that it does enable a kind of access that you’d never otherwise get. I mean, imagine even a prominent professor in the Catholic church being able to walk in pretty much whenever he wants to chat with the Pope? In a smaller, more tribal Mormon church that could happen, and as the church has become more corporate, the odds of that happening are increasingly small.

Certainly in light of my own family’s story here, I would never encourage people not to make the effort, even if it’s very quixotic. Because certainly the MX was quixotic in 1978.